Transcribing and Summarizing Genealogical Documents

Logs summarize your research activity. In addition, you will have your notes, analyses, and photocopies of what you found. Your notes contain all the details that do not appear on the logs. These notes include transcripts and abstracts of documents. Transcribing and abstracting are particular kinds of note-taking.

Genie Jargon

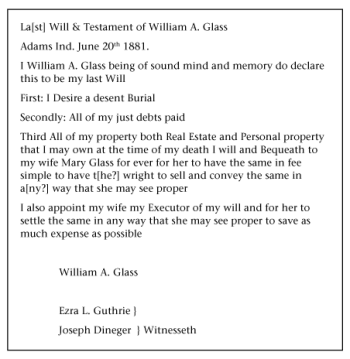

A transcript is a word-for-word exact copy of the text in a document. Nothing is changed; everything is written just as it appears: errors, punctuation, misspellings, and all.

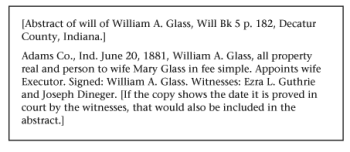

An abstract is a summary of the text of a document, retaining all its essential details.

Learning by Transcribing

Transcriptions are most useful when the document is very difficult to read (due to content or condition). It is also helpful when you are unfamiliar with the type of document, or when you have a particularly complicated or unusual document. You will be forced to transcribe if the fragile condition of the document restricts photocopying.

When you begin your research, it is helpful to transcribe all the documents you find relating to your family. The practice will assist you in becoming familiar with the old handwriting and will help you learn to recognize common phrases in similar documents. As your familiarity increases, you can switch to abstracting the documents except in selected cases.

Tree Tips

Read a document several times before you begin to transcribe or abstract. Difficult words or handwriting may become clear after several readings, making it easier to take notes.

You can hone your transcribing skills by visiting some online sites. Although the Board for Certification of Genealogists is aimed at individuals who want to become certified or for consumers wanting to hire a genealogist, the “test your skills” section is useful for all levels of researchers. You can print out two documents, transcribe and abstract them, and compare your results with the correct ones.

A particularly interesting site for learning to transcribe is www.dohistory.org/diary/index.html. Here you can transcribe right on your screen and compare your transcription with theirs. An interesting feature on this site is the “magic lens,” which magnifies portions of the document as your mouse hovers over words. Practice reading the handwriting without the aid of the magnifier and then get instant feedback by checking your work with the magnifier.

Abstracts: Summarizing the Document

For an abstract, you extract every detail that might shed light on your research problem. You are looking for all names, dates, places, and events. Examine documents carefully for unexpected information. A document may have a name that doesn't mean anything now, but may turn out to be a relative. Note any mention of a location; it may lead to other records.

Pedigree Pitfalls

If the name appears as Jas., do not convert it to James. The abstract is not the place for the interpretation. After you have examined all the records, then you can determine if the person is actually James. What looked like an “a” might turn out to be an “o,” and Jos. is the abbreviation for Joseph.

Although an abstract is a summary and does not include every word and punctuation mark in the document, it does include names and places just as they appear. If you think there is an error in a name or place (or anything else significant), you can include your correction or explanatory remarks in square brackets after the word. The brackets enable others to easily distinguish what was actually in the abstract, and what you added. It is permissible to correct simple words in the abstract; “funrale” may be corrected to “funeral.” It is important, however, to distinguish that some simple words can be corrected in the abstracts, but in the transcription the spellings are retained as they are in the original.

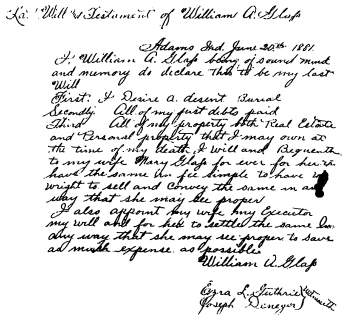

In the following figures you see a will from an actual probate file, followed by the transcript and abstract of the document. Compare the transcript and the abstract to the original document and then to each other. The transcript includes every word from the original; the abstract is a summary of the important information.

Did you think the name in the will was Glap? The last two letters are the “tailed s” and an example of how documents can be misread if there is not some familiarity with old handwriting. All spelling and punctuation are retained. When a word is not entirely legible or is partly gone (as are two words in this document), brackets are used.

Tree Tips

If ever in doubt as to whether something belongs in your abstract, include it. If it is something extra, it doesn't matter. If it is something you later need and don't have, it matters a great deal.

Although there are fill-in forms available for use in abstracting, they are constraining and not recommended. Trying to conform to the order on the form means rearranging the information from the document. In adapting the information to fit the form, omissions can occur or clues in the wording and order might be lost. I prefer to shorten the original while retaining the order of information in the document as closely as possible.

Learning the techniques for transcribing and abstracting is essential. Both are an integral part of genealogy research. Practice constantly, and examine various books of abstracts at the library when you are there.