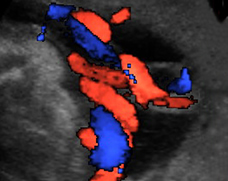

The umbilical cord, which connects your baby to the placenta, contains three vessels: two arteries, which carry blood from the baby to the placenta, and one vein, which carries blood back to the baby. The blood in the arteries contains waste products, such as carbon dioxide, from the baby's metabolism. Carbon dioxide is transferred across the placenta to your bloodstream and then to your lungs, where it's breathed out. Oxygen is transported from red bloods cells in your circulation, across the placenta to the baby in the umbilical vein. In addition to oxygen, the umbilical vein transports nutrients from the placenta to your baby.

The vessels in the umbilical cord have a protective coating called Wharton's jelly, and the cord is coiled like a spring so that the baby is free to move around. The coiling pattern of the cord has usually established itself by week nine and is usually in a counterclockwise direction. However, the cord can coil later, and sometimes isn't established until 20 weeks. The baby's movements seem to encourage the cord to coil.

The cord is usually attached to the center of the placenta, although sometimes it's attached near the edge. Very occasionally, it divides into its separate vessels before finally entering the placenta. The cord is usually under 1 in (1-2 cm) in diameter and 23 in (60 cm) long, which is twice the length needed to ensure that there are no problems at delivery.

After delivery, the cord vessels close by themselves. The arteries close first, helped by their thicker muscular walls. This prevents blood loss to the placenta from your baby. The umbilical vein closes slightly later (starting at 15 seconds, but only completed by 3 or 4 minutes). This allows blood to continue to return to your baby during the first few minutes of life. As a result, many feel that a slight delay before clamping the cord can be beneficial to the baby. There are no nerves within the cord, so cutting the cord after delivery is a painless procedure for your baby.